The famous American writer Mark Twain once said “Age is an issue of mind over matter. If you don't mind, it doesn't matter.” But, does age matter when it comes to fitting contact lenses? We’re often reminded that the world’s population is aging, and it’s expected that the proportion of the population aged over 65 years will more than double over the next 50 years. This suggests that the number of older adults wanting to be fitted with or to continue to wear contact lenses is very likely to increase.

There are a number of factors to consider when fitting contact lenses to older adults, as there is more to the aging eye than just presbyopia. A variety of changes to the ocular adnexa, tear film and ocular surface occur with age, which can influence the choice of lens material, lens design and overall suitability for contact lens wear. The availability of a variety of silicone hydrogel lenses has increased the options available to practitioners for fitting older adults.

Eyelids

Changes to the ocular adnexa with age include reduced elasticity of the skin of the eyelids, muscle tonicity and orbital fat [1]. The superior lid becomes less tight against the eye and sagging of the upper eyelid (dermatochalasis) is more common (Figure 1). These changes can lead to ptosis and narrowing of the palpebral aperture.

With age, the lower lids can also loosen from apposition to the globe (ectropion), which can be further exacerbated by contact lens insertion and removal procedures where the lid is pulled down [2]. The eyelids also become more wrinkled and the incidence of blepharitis and conjunctivitis increases with age, as the wrinkles harbour more bacteria [3]. Reduced eyelid sensitivity due to loss of nerve fibres also occurs.

Eyelid and punctal apposition are needed for efficient blinking and even distribution of the tear film across the ocular and contact lens surface. Inferior lid position is also important for proper orientation and movement of lenses and to help in preventing lenses from decentring inferiorly.

Tear Film

Dry eye is probably the biggest problem faced by aging contact lens wearers. Fifteen percent of the population aged 65 or over report at least one symptom of dry eye often or all the time [4] and it’s well established that dry eye is particularly common in women, and frequently occurs following the onset of menopause [5].

There is some debate regarding changes to the tear film and ocular surface with age; however, it’s generally accepted that tear production, tear quality and tear film stability decrease with age [6-9]. These changes can be attributed in part to degeneration of the lacrimal gland and its ducts [10], decreased conjunctival goblet cell density [2] and increased meibomian gland dropout with age [8].

Tear osmolarity also appears to increase with age, particularly in females [8, 11]. The lid changes discussed earlier can lead to incomplete blinks and incomplete eye closure during sleep, which can increase dry eye symptoms.

Cornea

The average corneal endothelial cell population decreases from approximately one million cells to about one third of that number by age 80 [12]. Polymegethism (variation in cell size) and pleomorphism (change in cell shape) also occur as a normal part of aging [12, 13]. The mean area of endothelial cells approximately doubles between the ages of 20 and 80 years.

As a result, endothelial pump function decreases with age and corneal edema recovery rates are significantly slower in older patients compared to younger patients [14, 15]. The cornea also becomes less effective at eliminating waste products, for example, arcus senilis develops as a result of deposition of lipid droplets in the stroma (see Figure 1).

|

| Figure 1: Typical age-related changes including sagging of the upper lid, loss of the normal upper lid crease, eyelid wrinkling and arcus senilis. |

click to enlarge |

Increased coverage of the superior cornea due to droopy upper eyelids can increase superior corneal hypoxia. Oxygen supply from the palpebral conjunctiva is also reduced with age, reducing the amount of oxygen available to the aged cornea during eye closure [16].

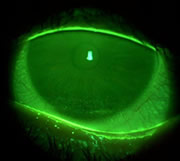

Increased corneal fragility and reduced corneal sensitivity are also observed with age, particularly after the age of 50 [17]. Wound healing is also slower [18] and there is an increased incidence of corneal fluorescein staining with age, particularly inferiorly (Figure 2) [19].

|

| Figure 2: Inferior corneal fluorescein staining, which is commonly seen with increasing age, particularly if lower lid apposition is lost. |

click to enlarge |

Pingueculae/Pterygia

Pingueculae and pterygia are more likely to occur in older eyes [1] and are most commonly observed nasally, but can also be seen temporally. Pterygia can affect the centration and movement of RGPs and pingueculae can affect fitting characteristics of soft lenses. Both can cause disruption to the tear film and wear of RGPs and soft lenses can cause additional mechanical irritation and desiccation.

Visual Function

Visual acuity (VA) reduces with age, particularly after the age of 50, and under low contrast and low luminance conditions [2]. Contrast sensitivity decreases for intermediate and high spatial frequencies and steroeoacuity is also reduced [20]. Older adults also suffer from increased glare sensitivity. Reduced transparency of the lens and cornea, retinal changes (rods, cones and retinal pigment epithelium) and reduced retinal luminance as a result of reduced pupil size, all contribute to the reductions in visual function [2].

Manual Dexterity

Older adults are likely to have more difficulty handling contact lenses, particularly if they suffer from conditions such as arthritis.

Systemic Disease

Older adults often have more systemic conditions (e.g. diabetes, arthritis, hypertension) and an increased intake of systemic drugs compared to younger adults.

Recommendations

Prior to fitting, a comprehensive eye exam should be conducted, including assessment of the ocular adnexa, tear film and ocular surface, and measurement of VA under low luminance conditions (particularly when prescribing multifocals). The side-effects of all medications should also be considered, as some medications may make contact lens wear more difficult (e.g. by causing dry eye). As with any patient, weigh up risks versus benefits of contact lens wear. The aging changes described above necessitate greater care when fitting contact lenses to older adults, but shouldn’t exclude older adults from contact lens wear.

Lens materials should be chosen to provide adequate oxygen transmission. Silicone hydrogels or hyper-Dk gas permeable (GP) lenses are good alternatives, particularly for higher prescriptions, multifocals and toric lenses. Decreased corneal and lid sensitivity can be an advantage for fitting GP lenses; however, age-related lid changes can make GP lens fitting problematic if lens position and translation are affected. Cosmetic lid surgery, which is increasing in popularity, can also affect GP lens fitting, by causing excessive lifting of the lenses with blinking. Silicone hydrogels can be better alternatives under such circumstances.

We still have a lot to learn with respect to tear film interactions with silicone hydrogel lenses. There is some evidence that the newer generation silicone hydrogels can decrease symptoms of dryness and discomfort; however, studies in elderly populations have not been conducted to date. Lens care routines should include thorough cleaning and rinsing to remove surface deposits and enhance surface wettability. Older patients should also be encouraged to use artificial tear supplements, preferably non-preserved, to assist with dryness symptoms. Tear supplements that can reduce tear film osmolarity may also be of benefit. Silicone hydrogels can also be used as therapeutic contact lenses to protect the cornea from desiccation when ectropion is present.

Handling difficulties can be overcome by prescribing lenses on an extended (EW) or continuous wear (CW) basis, prescribing thick lenses (such as silicone hydrogels) or recommending a lens remover/applicator. Lenses should also be tinted to assist with handling. Silicone hydrogels are a good EW option, as EW of GP lenses has been shown to induce ptosis [21]; however, practitioners should be careful about prescribing plus and toric lenses for overnight wear, due to reduced oxygen transmission through the thicker portions of the lenses. Older contact lens wearers should be reviewed more regularly, especially if wearing lenses on an EW or CW basis, as corneal sensitivity is reduced and they may be less aware of any corneal compromise. There may also be greater risk of developing sterile infiltrates if blepharitis or lid disease are present [22].

One silicone hydrogel multifocal has been released onto the market in some countries and others are expected in the near future. Custom made silicone hydrogels are also going to become more readily available. The increased demand for contact lens wear by the aging population is likely to drive the development of new lens designs that provide less compromise to vision and ocular health, and better comfort for older adults.

References

- Woods, R.L., The aging eye and contact lenses - a review of ocular characteristics. J Br Contact Lens Assoc, 1991. 14(3): p. 115-127.

- Benjamin, W.J. and I.M. Borish, Physiology of aging and its influence on the contact lens prescription. J Am Optom Assoc, 1991. 62(10): p. 743-53.

- Mancil, G.L. and C. Owsley, 'Vision through my aging eyes' revisited. J Am Optom Assoc, 1988. 59(4 Pt 1): p. 288-94.

- Schein, O.D., et al., Prevalence of dry eye among the elderly. Am J Ophthalmol, 1997. 124(6): p. 723-8.

- Mathers, W.D., et al., Menopause and tear function: the influence of prolactin and sex hormones on human tear production. Cornea, 1998. 17(4): p. 353-8.

- Furukawa, R.E. and K.A. Polse, Changes in tear flow accompanying aging. Am J Optom Physiol Opt, 1978. 55(2): p. 69-74.

- Hamano, T., et al., Tear volume in relation to contact lens wear and age. CLAO J, 1990. 16(1): p. 57-61.

- Mathers, W.D., J.A. Lane, and M.B. Zimmerman, Tear film changes associated with normal aging. Cornea, 1996. 15(3): p. 229-34.

- Patel, S. and J.C. Farrell, Age-related changes in precorneal tear film stability. Optom Vis Sci, 1989. 66(3): p. 175-8.

- Roen, J.L., O.G. Stasior, and F.A. Jakobiec, Aging changes in the human lacrimal gland: role of the ducts. CLAO J, 1985. 11(3): p. 237-42.

- Craig, J.P. and A. Tomlinson, Age and gender effects on the normal tear film. Adv Exp Med Biol, 1998. 438: p. 411-5.

- Laule, A., et al., Endothelial cell population changes of human cornea during life. Arch Ophthalmol, 1978. 96(11): p. 2031-5.

- Laing, R.A., et al., Changes in the corneal endothelium as a function of age. Exp Eye Res, 1976. 22(6): p. 587-94.

- Siu, A.W. and P.R. Herse, The effect of age on the edema response of the central and mid-peripheral cornea. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh), 1993. 71(1): p. 57-61.

- O'Neal, M.R. and K.A. Polse, Decreased endothelial pump function with aging. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 1986. 27(4): p. 457-63.

- Isenberg, S.J. and B.F. Green, Changes in conjunctival oxygen tension and temperature with advancing age. Crit Care Med, 1985. 13(8): p. 683-5.

- Millodot, M., The influence of age on the sensitivity of the cornea. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci, 1977. 16(3): p. 240-2.

- Millodot, M. and H. Owens, The influence of age on the fragility of the cornea. Acta Ophthalmol (Copenh), 1984. 62(5): p. 819-24.

- Norn, M.S., Micropunctate fluorescein vital staining of the cornea. Acta Ophthalmol., 1970. 48: p. 108-118.

- Brown, B., M.K. Yap, and W.C. Fan, Decrease in stereoacuity in the seventh decade of life. Ophthalmic Physiol Opt, 1993. 13(2): p. 138-42.

- Fonn, D. and B.A. Holden, Extended wear of hard gas permeable contact lenses can induce ptosis. CLAO J, 1986. 12(2): p. 93-4.

- Lemp, M.A., Is the dry eye contact lens wearer at risk? Yes. Cornea, 1990. 9 Suppl 1: p. S48-50; discussion S54.

|